In the 14th century BC, the Egyptians began construction on what would eventually become a nearly 2-miles long stretch of road called The Avenue of the Sphinxes, connecting two temples dedicated to the deities of their pantheon and the kings who were their earthly embodiments. The path would eventually be lined with more than 1,300 statues, most of them featuring the bodies of lions adorned by the heads of various pharaohs—the images of the gods.

During various festivals and celebrations, common people would parade down this road as a reminder that those in power were the exclusive image-bearers of the divine and that they decidedly were not. This was the dominant worldview not only in ancient Egypt but across the Ancient Near East. The gods imaged themselves through the powerful few while the peasant masses existed only to serve them. But Yahweh speaks a different word to his people Israel:

You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them - Exodus 20:4-5

God gives this instruction to the Israelites as they’re being liberated from Egypt around the 13th century BC, led out from beneath the shadows of the Avenue of the Sphinxes. After four centuries of mixing clay and straw, molding bricks, and constructing monuments imaging their oppressors and their deities, the people of God are freed from building images so that they might bear the image.

As the cultural pressure to achieve, succeed, and measure up mounts, we walk our own Avenue of the Sphinxes today, lined with images of modern-day gods peddling their various visions of the good life. These monuments demand our allegiance. This is why so many of us find ourselves worshiping at the altar of our desks. The writer Derek Thompson describes it this way:

“Workism is among the most potent of the new religions competing for congregants… the belief that work is not only necessary to economic production, but also the centerpiece of one’s identity and life’s purpose. [...] our desks were never meant to be our altars. The modern labor force evolved to serve the needs of consumers and capitalists, not to satisfy tens of millions of people seeking transcendence at the office.”

Even as religious affiliation has declined in the modern west (though the tide may be turning; more in a future post), we haven’t become less religious; we’ve simply redirected our worship. Secular work culture is fervently spiritual. Many seek “transcendence at the office,” a frantically searching for purpose by worshiping at various desk altars… landing the dream job… getting the raise… rising to the C-suite… the successful IPO… raising the perfect kids… crafting the perfect home… curating the perfect feed.

These and more are futile attempts at building an image. But such desperate striving is not only unnecessary, it’s antithetical to being human. We create not to become something we’re not; we create because we’re human. Namely, we create because we bear the image of a creative God.

In the beginning, God created… - Genesis 1:1

The word “create” is the Hebrew word bara, which is about much more than the material construction of a thing. To bara means “to bring order, give meaning and purpose, or to beautify” a thing.

In the beginning, God brings order, meaning, purpose, and beauty to, in the words of the Jewish scholar Everett Fox, the “wild and waste” of a disordered world. Then…

God said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.” So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. - Genesis 1:26-27

Tim Keller reminds us that, “Work is our design and our dignity.” Again, we do not labor in order to become; we work and create to bear the image of God, and bearing the image, living as Imago Dei, means joining God to bring order, meaning, purpose, and beauty to bear, as an expression of gratitude for who we already are. And sometimes, it isn’t until we get to the end of ourselves and reckon with the disorder all of our striving has wrought that we can finally join him there.

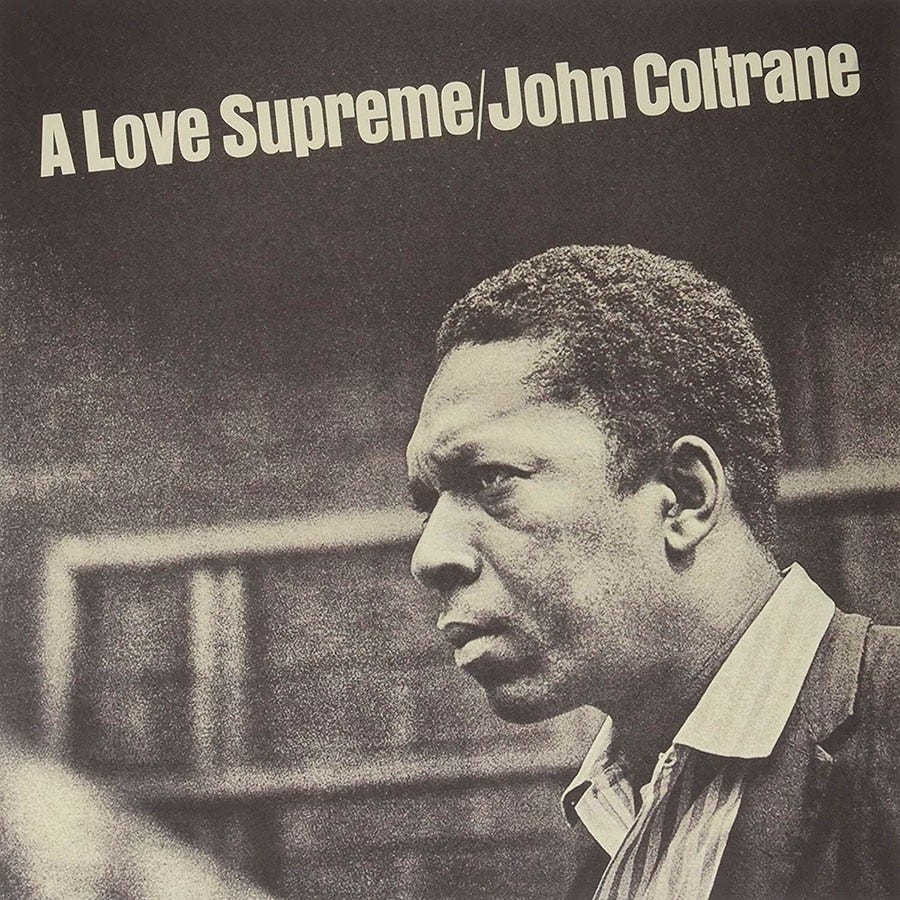

John Coltrane released A Love Supreme in 1965. The entire album was recorded in a single session at Van Gelder Studio in New Jersey. It went on to sell more than half a million copies and was nominated for two Grammy’s, making it one of the best selling and widely acclaimed jazz albums of all time. It was also John Coltrane’s most spiritual album.

After years of alcohol and substance abuse, Coltrane had had a spiritual awakening in 1957. He wrote and recorded A Love Supreme as a way of telling the story of God’s redemptive work in his life. In the liner notes, he wrote this:

“I would like to tell you that no matter what… He is gracious and merciful. His way is in love… It is truly a love supreme. This album is a humble offering to Him. An attempt to say ‘thank you God’ through our work… May He help and strengthen all men in every good endeavor.” - John Coltrane

Coltrane had experienced resurrection, brought out of darkness into light, out of death into life. And in expressive response, he created a work of brilliance and beauty, not out of desperate striving but as a means of grateful surrender. After years of struggling to build an image, John Coltrane found peace by bearing the image of the God who’d made him in love, for love. In so doing, he offered the world a true gift. And so can we.

Wow. Workism as a new religious icon. Powerful and thought provoking