Experts on the Truth, Dropouts on the Way

In Defense of Pastoral Nuance in a Negative World

Once upon a time, at least in the corner of evangelicalism where I first cut my teeth as a pastor, it seemed like everyone loved Tim Keller. His books, his sermons, his pastoral imagination, and missional perspective. But in recent years, the relationship’s gotten complicated.

Some say that Keller’s “winsome, third-way” approach only works for a world that no longer exists. The thinking goes that we now live in a “negative world,” that up to the early 90’s, culture at large viewed Christianity as generally positive; then from the mid 90’s until the early 2010’s, that view turned neutral; and since then, culture has turned and we now inhabit a “negative world” in which Christianity is repudiated and seen as a threat to the public good.

I’d suggest that just how negative a world we live in varies a great deal by region, city, church, etc. And I say this as a pastor living and serving in Silicon Valley, which is, statistically at least, one of the most unchurched, secular regions in the country. And though there are signs that the tide might be turning, even here, it’s far too early to tell in what direction.

Either way, let’s grant the shift and assume we live in a “negative world” (to varying degrees). In the past few years, in reactive response to this external cultural shift, significant momentum has been growing toward an internal pastoral shift—a shift away from nuance and toward confrontation. It’s been fascinating, and at times disheartening, to watch this swift turn play out in sanctuaries and on stages across the country.

“Why aren’t you angry?” That was a line in an email I received not long ago. Attached were links to clips and sermons of other pastors around the country who’d recently addressed a cultural moment I’d also addressed in our church. This person wasn’t upset because I believed the wrong thing. He was upset because I expressed it the wrong way. These other pastors were “angry,” so why wasn’t I? That was his reason for concern.

In my book Listen Listen Speak, I explored the way today’s media ecosystem has been carefully designed to amplify agitation. In the past decade, overall media consumption has risen more than 20 percent and daily smartphone use has ballooned from 45 minutes to over 4 hours. That’s a lot of agitation. And the machine knows that anger and outrage are what keep us most engaged. Our fracturing is the fuel that keeps the machine running.

Hostility is the primary currency being bought and sold in a digital market where we are the products. But online discourse isn’t always accurately reflective of real life. Beyond the noisy few await the quiet masses eagerly desiring nuance. The data actually tells us that “a majority of Americans… are fed up by America’s polarization… they want to move past our differences.”

As tempting as it might be for pastors and church leaders “bow up” against what might feel (especially online) like the unified, collective aggression of culture at large, when we do so, we unintentionally participate in the cultural tide of anger, outrage, and hostility that the peculiar, paradoxical way of Jesus intends to resist and upend.

The argument for a more confrontational approach in a “negative world” usually begins with the idea that “the Gospel is offensive” and it is. But the Gospel is offensive in every way. In a world where anger feels like courage and outrage feels like strength, nuance is itself offensive. Gentleness is subversive. Empathy is resistance. Kindness is rebellion. These are not weak alternatives to truth. They are the way of Truth himself.

The truth of the Gospel confronts and disrupts the truth claims of culture. Culture says, “Be true to yourself. Your truth is your truth.” The Gospel declares, “There is one Truth, embodied in Christ and expressed through Scripture.”

And in much the same way, the way of the Gospel also confronts and disrupts the way of culture, which amplifies antagonism and demonization. The Gospel’s naturally offensive response is not to imitate the hostility. The way of the Gospel offends cultural antagonism through kindness and goodness. The way of the Gospel confronts demonization through the painstaking work of humanization.

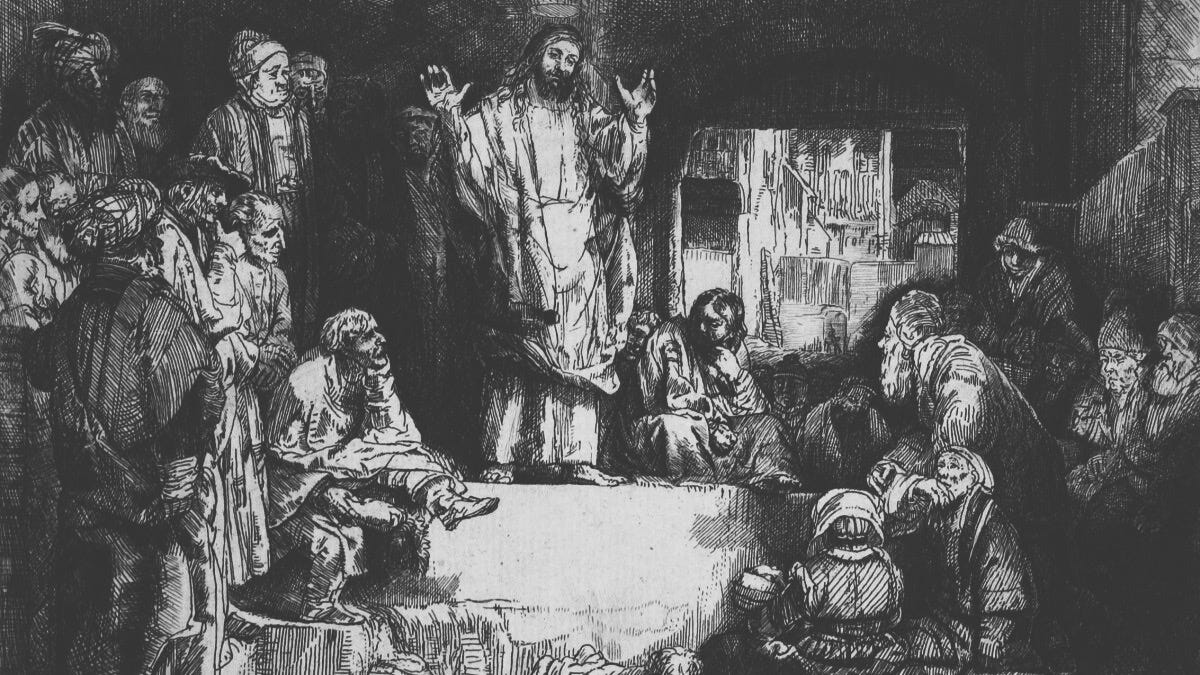

Eugene Peterson once wrote, “Jesus is the Way as well as the Truth. The way the gospel is conveyed is as much a part of the kingdom as the truth presented. Why are pastors experts on the truth and dropouts on the way?” Pursuing at least a passing grade in pastoral nuance remains essential. We must not be content to be experts in truth while flunking in the way.

In my experience in Silicon Valley, the way we offer truth is often the difference between someone opening up or closing off to the possibility that this truth might lead to life. Marshall McLuhan’s line, “The medium is the message,” applies here, and pastors would do well to take heed.

Jesus is the Way, the Truth, and the Life. And it is Jesus we follow. So may we carry truth into the world, may we carry it in the way of Jesus, and may many, compelled by the truth and the way of Jesus, move toward life.

I have Kari’s questions (below), as well. But the more I consider them, the more complicated and situational they appear to be. How do we weigh and address the “stronger” and “weaker” brothers and sisters at the same time we’re pursuing unity? How do we refrain from scapegoating while retaining a prophetic voice in love? Conscience and conviction are things that should be respected, whether the conclusions are right or wrong. Nuance is real and we’re all (hopefully) just trying to honor what glimpses of God that we’ve experienced and acquired in our lives. How do we toe the line on protecting unity while also speaking with prophetic conviction in the name of advancing Biblical justice? Ethics is a tricky thing. And the more I think of it, the more it requires prayerful community discernment via the Holy Spirit’s leading. And with that, I think we need to instruct our congregations on what freedom in Christ means vis-a-vis Matthew 18, Galatians 5, and Romans 14. Otherwise, we won’t be prepared for the task ahead.

I agree with your points here, but as a related question, when/where does the idea of righteous anger at injustice, oppression against "the least of these," etc. fit into this idea? Is it that pastors, because of their public role, should not express that? Or should none of us, because that is only for the Lord Himself to express? Curious what you think.